Newsletter Subscribe

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

22nd – 29th July | Naryn to the Ken Sai Border Post (Kyrgyzstan/Uzbekistan) | Distance: 525km | Total Distance: 7801km

We had been enjoying some cooler temperatures in the altitude of the Tien Shan, but leaving Naryn, at around 2000m altitude, it had warmed to 34C. I enjoyed following some better asphalt roads albeit with some long stretches of road works. For most of the day I rode through a broad valley, several kilometres wide. To the north, towering above the river, a range of high mountains with a lower wall of white, weathering cliffs and badlands. Nearer to the road was another range of rugged mountains. About 40km from Naryn was small gorge where the river had been dammed for a hydroelectricity system that supplies a quarter of the region with power.

The plan was to continue to the village of Ak-Tal (88km) and on to Ugut, keeping to the south side of the river. Google Maps showed a significant road with a 2350m pass on the way to Kazarman. The road however dropped in quality after Ugut. Then, after 111km we were stopped by some workmen in a truck who told us the road stops completely in a few kilometres and there was no way through. It’s not the first time Google has been completely wrong. We had to return 23km to Ak-Tal and take the only other option, a road given the tag “Kyrgyzstan’s most scenic road.” It was actually the road I originally planned to do, but because of the high pass and my digestive tract issues that were sapping my energy, I had opted for ta supposedly easier route. Now I had no choice but take the higher road. In order to keep to my schedule I needed to reach the next town, Kazarman, in two days. From Ak-Tal, I belted out a further 17km along a rough gravel road to get to where the climb started and give myself a chance of reaching Kazarman.

The only way was up from our campsite (at 1620m) – quite steeply for the first 2 km, then after 5 km some respite with 4 km of asphalt through a village, then rough gravel again. After crossing a river, I settled into climbing a long straight with, on average, a 5% gradient heading directly towards the mountains.

I was pleased, and relieved, to make the summit at 2768m, an ascent of 1200m over 29km! (1800 vertical metres climbed). Not a bad lunch spot!

My day then got much tougher again. There was no nice valley gradually descending to the Naryn River – the road crossed several 200-300m passes. Into a strong headwind and often loose gravel, this was a particularly difficult section. It was soon evident that I wouldn’t make it to Kazarman in one day – I just tried to get as close as possible. After 70km, I was totally drained and we were running out of light. I made it to a small village, Kosh-Bulak but no one there was offering accomodation, so we drove 5km to the next village where a family, who sometimes offer accommodation, put us up.

I had to pass on the dinner offered and requested mashed potatoes – something that I could possibly digest in the hope of having more energy in the morning.

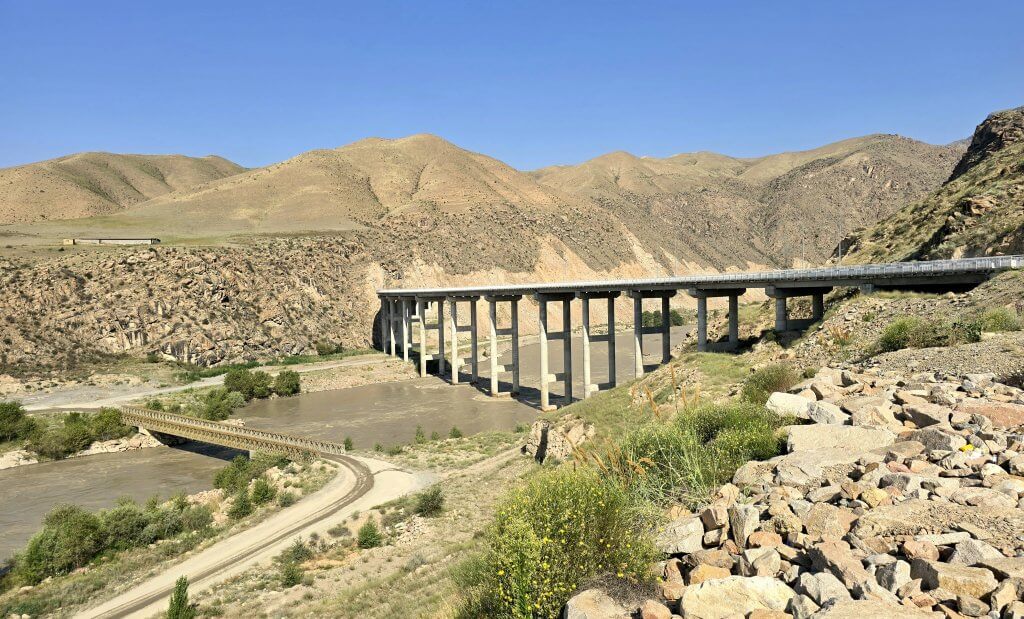

We drove back to where I stopped cycling and I continued to Kazarman. There was just one more 300m climb and then a downhill, through a spectacular gorge to the Naryn River. As we were half a day late, we were just going to replenish our supplies, get some medication for me and move on. However, I had pushed past my limits over the last couple of days and decided to take the afternoon off. I slept for four hours!

While we were having lunch, Sasha found out there had just been a landslide on the route we were about to take, through Naryn Gorge. He and Anna went to investigate while I rested. The road was closed and at this early stage, we didn’t know when it would reopen. There was only one alternative route and it wasn’t following the Naryn River as I had planned.

I was feeling a little better the following morning, but still low on energy. We drove to the entrance of the gorge where the road was closed to find out more information. The mayor was inspecting the landslide. Anna had sent our drone to see what the problem was. The landslide was about 5km from the main bridge. It was a new road and apparently this wasn’t the first landslide – but it was a big one. The mayor and police said the road would remain closed for at least 4 days. We were hoping we could use the old road to pass the problem, but the police were adamant we could not pass. (In fact, the road has now been closed for 10 days, and it will be longer before the area is cleared and the rocks stabilised.)

By then I had devised Plan B, to cross the high pass between Kazarman and Jalalabad (151km route, 3000m pass). Then, as my journey is meant to be following the Naryn River from its source to where it becomes the Syr Darya as much as possible, I would cycle to the border crossing nearest the Naryn River and then we would drive back up the river to see a couple of important sites that I didn’t want to miss entirely, before crossing at the border into Uzbekistan.

Starting in Kazarman in 35°C temperatures, it was basically up from the Naryn River – thirsty work until I got higher. There was only half a day left by the time we got going, so my aim was to do half of the pass, up to 2000m on the first day, and then the final 1000m climb on the second morning before seeing if I could reach Jalalabad.

It was slow going with my low level of energy but I just kept chipping away. The climbing was mostly 5-6% gradients with some steeper pinches on a busy gravel road. The dust was unpleasant and I was constantly having to pull my neck buff over my mouth the nose. After reaching 2100m I descended to a valley and to our surprise, a large Chinese factory with a lot of construction going on. There were trucks and diggers all through the previously pristine valley.

I continued for a further 5km while we searched for a campsite and then returned to the stream, a little away from the factory to camp.

The final stage of the climb was the steepest, the road wriggled its way around the mountain with a series of switchbacks. The steepest gradient I measured was 15%, but mostly it was between 6-8%. The quality of the gravel road was pretty good and I was pleased to reach the summit of Sholunar Pass in under three hours.

The descent was not as much fun as I had hoped thanks to the stream of Chinese trucks, some of the drivers quite aggressive, and the thick dust they stirred up every time. 16 km down the pass, the Chinese were building a train tunnel. The whole valley was a mess with construction sites along the way and so much bulldust. The ride remained challenging over rough, dusty roads, and more shorter ascents until I reached the 60 km mark. Suddenly I entered farmland – open fields of harvested wheat and other crops – and a tarmac road.

After 68 km, I didn’t think I was going to make Jalalabad, but once I hit the highway, there was a very gentle downhill and good road most of the way. Entering the city, there was a terrible section of roadworks for about 6 km where I battled with trucks and dust. I made it just after sunset.

Finally an easier day crossing along the eastern rim of the Fergana Valley on good road to the border crossing into Uzbekistan. Back down to 600m above sea level, the temperature was back up to 35°C. I made the distance by 4.30 pm so we had plenty of time to start the drive back up the Naryn River. I was looking forward to a day off the bike to visit the village of Kyzyl Beyit and later, Toktogul Reservoir.

When the Naryn River was dammed by the Soviets in 1974 to create a massive hydro-electric scheme, Kyzyl Beyit and some other settlements were totally cut off from the main road and all ammenities and 20,000 people were displaced. The village had to fend for itself – no access roads, communications or electricity. Only in the last three years have the Chinese built a track through the mountains so they can access a mining site and extended the track to link Kyzyl Beyit. To reach Kyzyl Beyit, we had to negotiate a ferry trip across the water, on a pontoon boat made by the villagers, then one villager in a Russian Lada car would drive for an hour to meet us and take us to the village.

Kyzyl Beyit is a village of about 350 people – each family has 8-10 children and there are about 35 houses strung out over about 3km. We visited one family at the top of the village and another at the bottom. Life here has changed massively since the road was pushed through and the government provided solar power panels for each house. Before then there was no electricity, no means of communication and access was by the boat only. It was an 8km trek, on foot or by horse, to and from the Naryn River. Now the children can leave to go to school, villagers can communicate by mobile phone and they can get medical assistance more easily.

There is a little more to these stories but I am very short on time and need to publish this blog.

Thanks to ZeroeSixZero, you can open this link on your phone and select “add to home screen” and the map will become and app. You can then keep updated in real time.

Support my Water.org fundraiser to help bring safe drinking water and sanitation to the world: Just $5 (USD) provides someone with safe drinking water or access to sanitation, and every $5 donated to my fundraiser will enter the donor into the Breaking the Cycle Prize Draw.

An education programme in partnership with Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants, with contributions from The Royal Geographical Society and The Duke of Edinburgh’s International Award Australia. We have created a Story Map resource to anchor the programme where presentations and updates will be added as we go.