Newsletter Subscribe

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

We caught up on the 16th of October at four in the afternoon. Both in our offices, both surrounded by unfinished business. I was in Cologne, watching the light fade across the river. Thomas was somewhere in Switzerland, buried deep in a workshop that hadn’t known silence for weeks. Between us, the connection crackled with the sound of compressed air, a distant rattle of tools, and the steady hum of a man racing a clock he had set for himself.

He laughed when he picked up. That kind of dry, weary laugh that belongs to people who are doing too much and know it … but wouldn’t have it any other way. Three customer vehicles finished on Monday, he told me. One show car due this weekend. Then, maybe, a little breathing room for the Quartermaster project. The one bound for Dubai.

I imagined the scene: aluminium panels stacked against the wall, sparks still warm on the floor, and a black Grenadier sitting centre stage like a beast in mid-transformation. Around it, tools, jigs, cables, and a sense of quiet defiance. Black Sheep Innovations isn’t known for half measures. They build things that work, things that last. But this time, the bar was set even higher.

“We’re not just building another expedition truck,” he said. “We’re building something that proves what’s possible—even under pressure.”

The first Sheepmaster, built a couple of years ago, had been a revelation, but also a warning. It did everything it was meant to do: rugged, comfortable, self-contained. But it was heavy. Too heavy for Thomas’s taste. The new Quartermaster, Sheepmaster Two, would be different: stripped of excess, engineered to the gram, and focused on function.

“Every kilo matters,” he said. “When you’re overlanding, weight is the enemy. You learn that the hard way.”

This time, aluminium takes the lead. Not just in panels, but in the logic of how those panels come together. The structure is lighter, but stronger—overlapping, interlocking, folding into itself like a puzzle. Four walls and no full floor, just a rigid box that owes its strength to geometry as much as material.

Then there’s the clever part, how he uses the necessary kit as part of the design itself. The Maxtrax recovery boards aren’t simply bolted on; they’re recessed into the bodywork, each set sitting in a shallow cradle that doubles as a structural brace. The jerrycans, too, are half-sunk into the aluminium walls, their forms stiffening the box while providing vital fuel storage.

“People think of design in terms of aesthetics,” Thomas told me, “but for us, it’s always structure first. If you can make something functional and beautiful, great. But every curve, every recess, has to earn its place.”

He’s right. Look at the build long enough and you start to see it: a philosophy of economy, where nothing exists for show. Even the cut-outs and folds add stiffness. The result isn’t flashy. It’s purposeful. And that’s where the beauty lies.

When he says “lightweight,” he doesn’t mean fragile. The rig is still built to take punishment. But rather than relying on thick plate and brute strength, he’s rethinking the way the structure carries its load.

The roof supports an Intrepid Geo 3.0 hard-shell tent, but even that has been re-engineered. The tent floor has been removed to create a direct access from the shell below. There’s no need to step outside in wind or rain. Gas struts will lift the bed, creating standing height and giving the space a sense of volume that’s rare in compact expedition setups.

Inside, the bed frame is still a work of mental engineering. It has to fold, tilt, and shift to make space for two people. “It’s not just furniture,” Thomas said, “it’s choreography.”

Under the flatbed lies a masterpiece of packaging. When he first looked at the Grenadier’s chassis, he saw wasted space between frame and floor. To most builders, that void is too shallow to be useful. To Thomas, it was an invitation.

He spent two weeks measuring, adjusting, mocking up components until everything fit with millimetre precision. Into that space went an 18-litre air tank, air horns, a diesel heater, dual freshwater tanks (32 litres each), a pull-out kitchen box from MOKUBO, and additional storage modules—all neatly mounted on slides that extend a full metre and a half from the rear.

“We’ve got maybe two or three millimetres clearance left,” he said, almost proud. “But everything fits. It’s tight, but it works. And when it works, that’s a good feeling.”

A fold-out stair system tucks beneath, ready to deploy when needed. Every corner serves a purpose. The goal is not to show off, it’s to make sure that no space goes unused and no weight is wasted. Even the smallest detail is guided by an understanding of what happens when you’re thousands of kilometres from home and the terrain stops forgiving mistakes.

Step inside the cabin and the same thinking continues. The rear bench is gone. A clean sixty-five kilos shaved straight away. In its place sits a partition and a practical workspace: a fridge on one side, a Milwaukee tool array on the other.

“We’ll be out there for weeks,” he said. “We need to be able to repair whatever breaks, wherever we are. There’s no calling a service truck.”

Milwaukee joined the project as a partner, providing a full suite of cordless gear. It’s a small victory in a build otherwise powered by sweat equity and long hours. “Sometimes,” he added, “when people believe in what you’re doing, they make the impossible a bit more manageable.”

Up front, new aluminium mounts are being machined for laptops, cameras, and comms devices—designed to match the cockpit’s lines rather than clutter them. The Delta Bags seat covers are already fitted, and five-point harnesses are coming next. Not for show, but for posture. “When you drive long distances, you start to collapse into the seat. This helps keep you upright. And, yes, it looks a bit like rally spec,” he admitted with a grin.

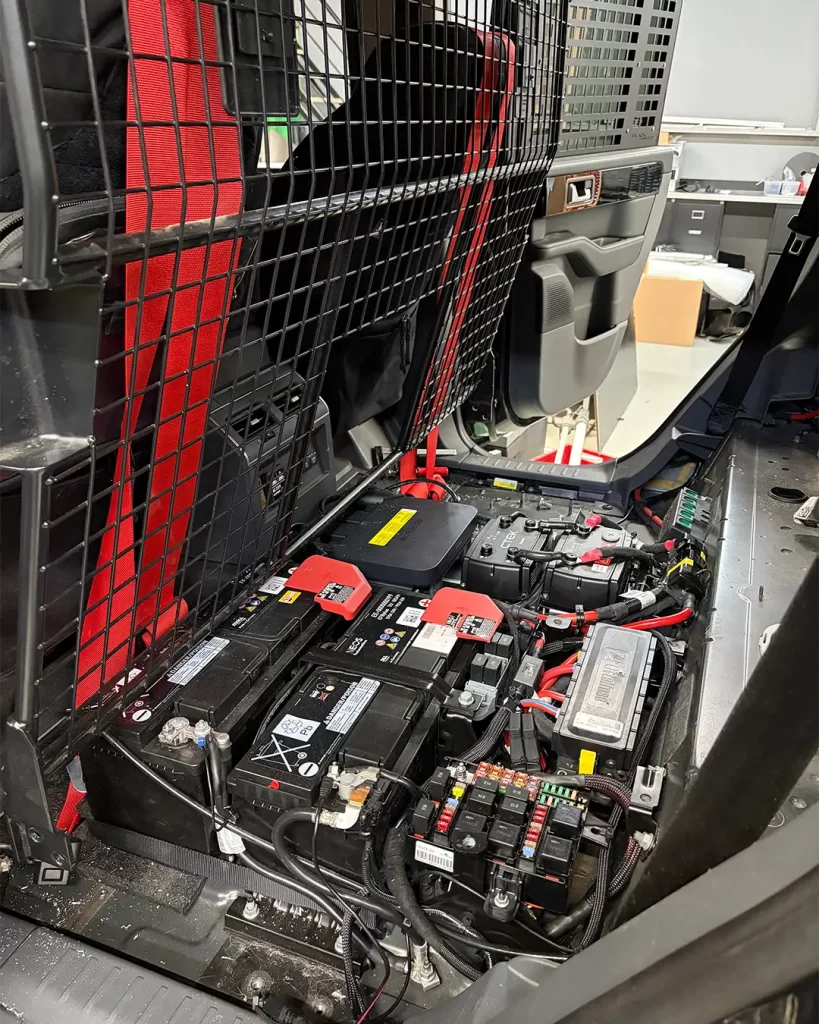

Modern vehicles are ruled by electronics, and the Grenadier is no exception. But Thomas treats electrical systems the same way he treats everything else: understand it, simplify it, make it work.

“We’re not fans of the factory wiring,” he said bluntly. “It’s overcomplicated. Too many shared circuits. But you can’t just rebuild it—it’s too deep.”

Instead, they’ve re-routed what they could, lifted the looms higher to protect them from the terrain, and added layers of redundancy. The onboard power comes from an EcoFlow Delta 2 Max, fed by roof-mounted solar and an alternator booster. If the main batteries go down, the EcoFlow can backfeed and jump-start the system.

That’s independence … not in the romantic sense, but the practical one that keeps engines turning when things go wrong.

He’s also testing a Global Guard OBD module. Developed in Switzerland, it lets his workshop monitor the vehicle remotely in real time. Engine data, transmission behaviour, even fault codes can be read and reset from home.

“It’s the first one made for the Grenadier,” he said. “Our workshop can watch it live while we’re driving through Iran or the Emirates. It’s a safety net, but also a glimpse of what’s coming for modern overlanding.”

And as for INEOS? He just laughed. “They like what we’re doing, privately. But officially? Nothing. Not even a sticker. That’s fine. Independence cuts both ways.”

The Sheepmaster stands taller than most (other than those fitted with portals). That’s partly because of the prototype rally suspension that’s about to go in. A system worth eight thousand euros, built to take the punishment of high-speed gravel and corrugations. Massive dampers, heavy-duty Eibach springs, and travel figures that will make even seasoned off-roaders raise an eyebrow.

“It’s only been fitted once before,” Thomas said. “We’ll be the first to test it properly. Expect about seven centimetres lift, maybe more once it settles.”

The Invictus alloy wheels, flown in from the US, complete the stance. Ultra-light but rated to carry fifteen hundred kilos each, they feature integrated air-release valves and the sort of machining you usually see on aerospace parts.

Beneath, the belly is armoured in 12mm aluminium—doubled to 24mm in impact zones. The Black Sheep rock sliders and stainless mid-plates are designed to take abuse without complaint.

“If something breaks, we can unbolt and replace it,” he said. “So far, nothing has.”

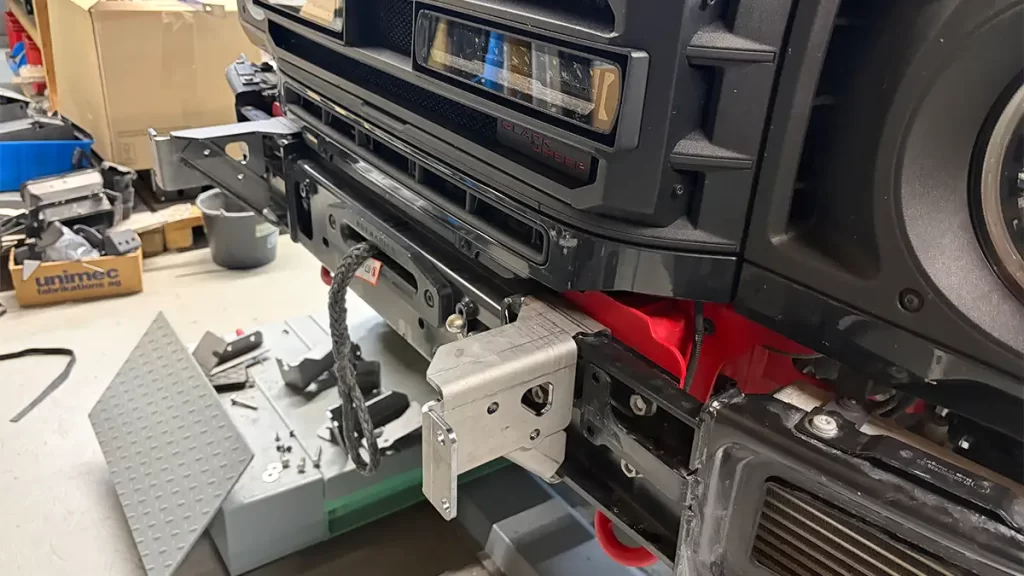

Up front, a removable Australian bull bar is on its way. If it arrives in time, it’ll be a bolt-on accessory — something travellers can mount for expeditions and remove for legality on European roads. A factory winch sits ready behind the bumper, because if you’re travelling solo, you plan for self-recovery, not rescue.

Inside the box, the walls are 30mm insulated panels covered with felt … warm to the touch, soft enough to turn aluminium into something habitable. Hidden behind the side-mounted Maxtrax are concealed windows, invisible from outside. Security sits high on the priority list, especially when you’re parked up far from civilisation.

Even the door locks are unconventional. Some are the kind you’d find on a gun safe rather than a camper. “You can’t stop everyone,” he said, “but you can slow them down.”

There’s a quiet logic to it all. Not paranoia, just preparedness. When you’ve spent months building a home on wheels, you don’t want it broken into for a packet of biscuits and a phone charger.

At the back of the cabin, the furniture is almost non-existent, by design. Instead of plywood or composite cabinetry, Thomas uses Tradom (formerly Tread) storage boxes, the heavy-duty polymer crates better known for strapping to roof racks. Three sit side by side, connected so that their lids open in unison. It’s modular, indestructible, and easily replaced.

“They’re overbuilt for off-road use,” he explained. “You can sit on them, sleep on them, throw them off a truck. And they link together, so you can open all three at once. It’s brilliant.”

Black Sheep is now importing the boxes directly, with plans to distribute them across Europe.

“They’re too good to keep to ourselves,” he said. “And soon, Maxtrax will have a European base in Holland, so things will move faster.”

There’s a moment in every call with Thomas when the conversation slows, when the technical talk fades and the man behind the metal takes over. You can hear the fatigue in his voice, but also something else: pride.

“It’s chaos,” he admitted. “But it’s good chaos. We’ve got maybe two weeks left. The list keeps changing, but that’s fine. It’s always like this before a big journey.”

He’s not one for corporate polish. There are no slogans, no speeches about brand alignment or marketing reach. What he builds is born from use, not theory. And that’s what makes it worth writing about.

Before we ended the call, I asked if he ever wonders why he does it—the long nights, the deadlines, the endless tinkering. He paused for a moment, then laughed again, the sound of a grinder sparking somewhere behind him.

“Because it’s what we do. We build. We test. We push. And when it’s done—when it all works—that’s the moment that makes it worth it.”

The connection faded, replaced by the steady whirr of the workshop. Somewhere in Cologne, I closed my notebook and smiled. The beast was coming to life—not through hype or sponsorship, but through the sheer will of a man and his team who refuse to settle for “good enough.”

In a few weeks, Sheepmaster Two will roll into Dubai. And when it does, it’ll carry more than just tools and gear. It’ll carry proof that craftsmanship still matters … that true adventure starts not on the road, but in the workshop, long before the dust ever hits the tyres.

Follow their journey as it unfolds on Instagram