Newsletter Subscribe

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

The true source of the Oxus/Amu Darya has been a matter of conjecture for at least 200 years; since the Great Game when imperial Britain and Russia competed for control of Central Asia (as detailed in Blog 28).

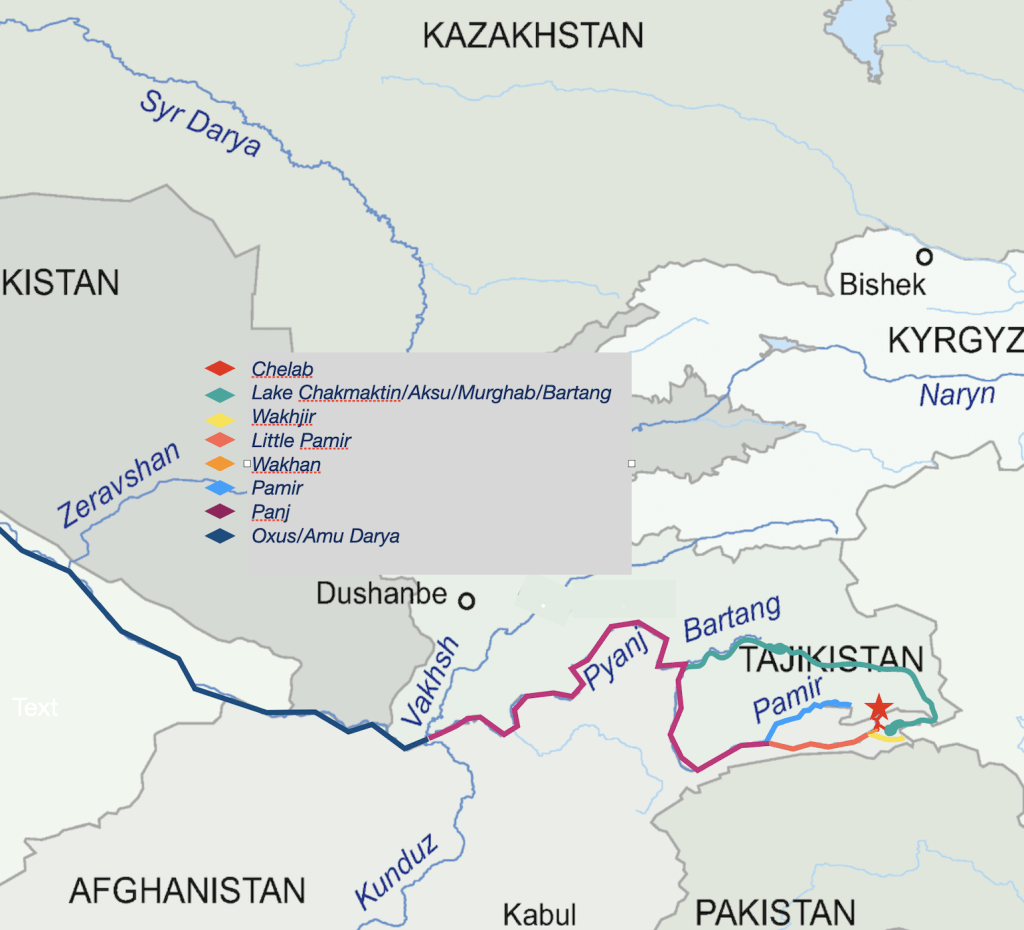

Created in the late nineteenth century at the conclusion of the Great Game, the Wakhan Corridor served as a buffer between the territories of the British and Russian empires. The two empires agreed that the true source of the Oxus would mark the border between their territories. Several sources of the river were identified – Lake Zorkul (then named Lake Victoria by Lt Wood, 1858), the ice cave at the head of the Wakhjir River (discovered by Lord Curzon, 1893) and Lake Chakmaktin. However, the true source was never located.

In 2007, Bill Colegrave led an expedition in search of the true source of the Oxus and concluded that it was the head of the Chelab, a stream flowing down from the Nicholas Range (Named after Tzar Nicholas II during the Great Game). Unusually the stream bifurcates; the west-flowing branch enters the Little Pamir (or Bozai) River (which 15km later flows into the Wakhjir to become the Wakhan River and then joins the Pamir River to become the Panj River), the east-flowing rivulet ends up in Lake Chakmaktin (out of which flows the Aksu/Murghab/Bartang tributary that enters the Panj River at Rushan). The point at which the Panj River is joined by the Vakhsh River is the beginning of the Oxus/Amu Darya. This means water from the Chelab flows into the two main tributaries of the Oxus. Therefore, the source of the Chelab should be considered the true source of the mighty Oxus River.

However, while Bill had identified the Chelab Stream as being the true source, he had only been as far as where it bifurcates and encouraged me and my team – Rupert, Malang and Adrian – to follow the stream and its tributaries to discover the true source of the Oxus.

The plan was to start the trek from Aqtashtoq, a winter settlement belonging to the Kyrgyz clan who live and graze their animals in the region, including the Chelab Valley. It’s only about four kilometres from where I ended the cycle expedition and near to where the Chelab Stream bifurcates. At 4117m elevation, this is the lowest of their settlements where they live out the bitterly cold winters. Being the end of summer, the camp was empty apart from three men who were cutting and stacking slabs of dung, their essential fuel source, in preparation for winter.

After a stodgy lunch of 2-minute noodles (again) we ventured across the pamir (high plain) to the main summer camp. We needed to buy bread for the trek and it is always good practice to speak to and learn from the people of the land. Between the two settlements there was a rough track that crossed the smaller west stream (after the Chelab bifurcates) and stayed on higher ground – much of the pamir is swampy due to a network of tiny waterways, making the land surface very boggy.

En route we tried to locate the watershed, a higher point in the landscape where no water flows across it. The watershed determines the direction of the water flowing off it – streams on the west side of the watershed flow west, to the Little Pamir River, and streams on the east side flow to the east, draining into Lake Chakmaktin. It is a particularly important landmark relating to the bifurcation of the Chelab – the land feature that forms a barrier to the Chelab Stream and may have caused it to bifurcate. Due to the complexity of the landscape, including the conundrum of rivulets on the Little Pamir, the watershed is particularly difficult to define. We didn’t locate it exactly at the time but by studying satellite maps later, and with the team’s observations, I think I may have worked it out – if so, we were within 150m of driving over it. This needs further investigation before anything is published.

Back at Aqtashtoq, the donkey handler and his two donkeys had arrived. Malang had hired him in Sarhad. From there the donkey entourage immediately began the 80km trek. They started at 2.30am in order to make it in time the next day (40km a day on foot).

We set off at 7am from Aqtashtoq, the donkey man leading the way up the west side of the Chelab. There was a faint track for the first three kilometres leading to the community’s autumn camp. It is important for the Kyrgyz to keep their stock moving to new pastures so not to overgraze any regions. Judging by the lush grass in many places, the animals were not short of food.

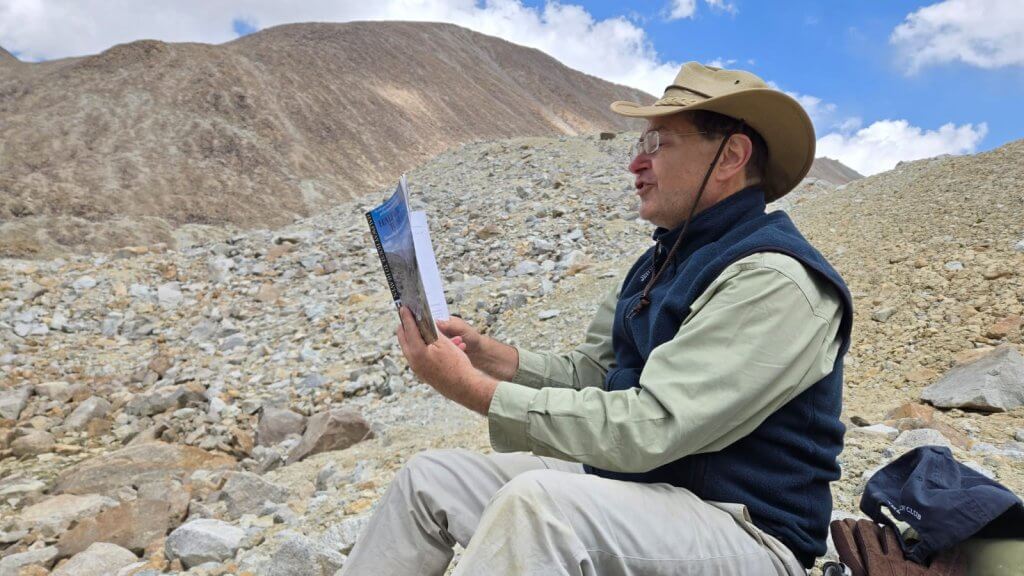

With my highly qualified team I was confident we would collectively make the correct decisions in the search for the true source of the Oxus/Amu Darya. Rupert has very considerable geomorphological experience and has surveyed rivers including the Nile, Mississippi and the drainage of Kenya’s Lake Turkana. Malang, the first Afghani to climb Afghanistan’s highest peak, has been coming to the Little Pamir for about 20 years, although he had never been up the Chelab Valley, and watched the glaciers’ considerable decline. Adrian has trekked and climbed some of the world’s highest peaks while filmmaking, including just over the border in north Pakistan. I also have a background in geography.

After 6.5km we reached the confluence of the two tributaries that form the Chelab Stream. At this point we had to decide which stream to follow; which was the bigger stream. I had measured the length of both streams on Google Earth and, although things can look a bit different on the ground, I had at least ascertained that they were of a similar length and altitude; the west stream being about 300m longer.

Standing near the confluence, it seemed obvious that the west stream was the more significant waterway. It appeared as though the east stream flowed into the bigger west stream.

While I had two experts in Rupert and Malang with me, who have serious credentials in understanding how to determine river sources, any layperson could easily see which was the principal stream here. It was an easy decision. We unanimously agreed that the west stream, due to its apparent size and volume, was the one to explore. We followed the Chelab Stream as it veered left and a kilometre later found an idyllic camp spot near the water.

We had planned to head for the source on the first day to give us the possibility of exploring the other tributaries the following day, but as a team we were too slow. Rupert was unwell and could not keep even half of our pace. With the waters rising in the afternoon due to the daily glacial melt, and time not on our side, we made the decision to head back to camp and get a very early start the next day. Before doing so, Adrian (filmmaker), who is a very strong trekker and mountain climber, crossed one of the bigger tributaries and did a recce to check what was ahead, at least for the next section of the valley. We especially wanted to know whether there were any major obstacles to negotiate.

Rising at 4am, breakfast, as had been the usual fare since Ishkaskim, included tea, bread (bought from the Kyrgyz community), long lasting cream cheese and jam. We decided to break into two teams; Adrian, Malang and I headed straight towards what we believed would be the source of the Chelab. We needed to focus on the filmmaking aspect too, which takes extra time. Feeling much better, Rupert trekked with the donkey team so he could concentrate on monitoring the many streams and glacier geography.

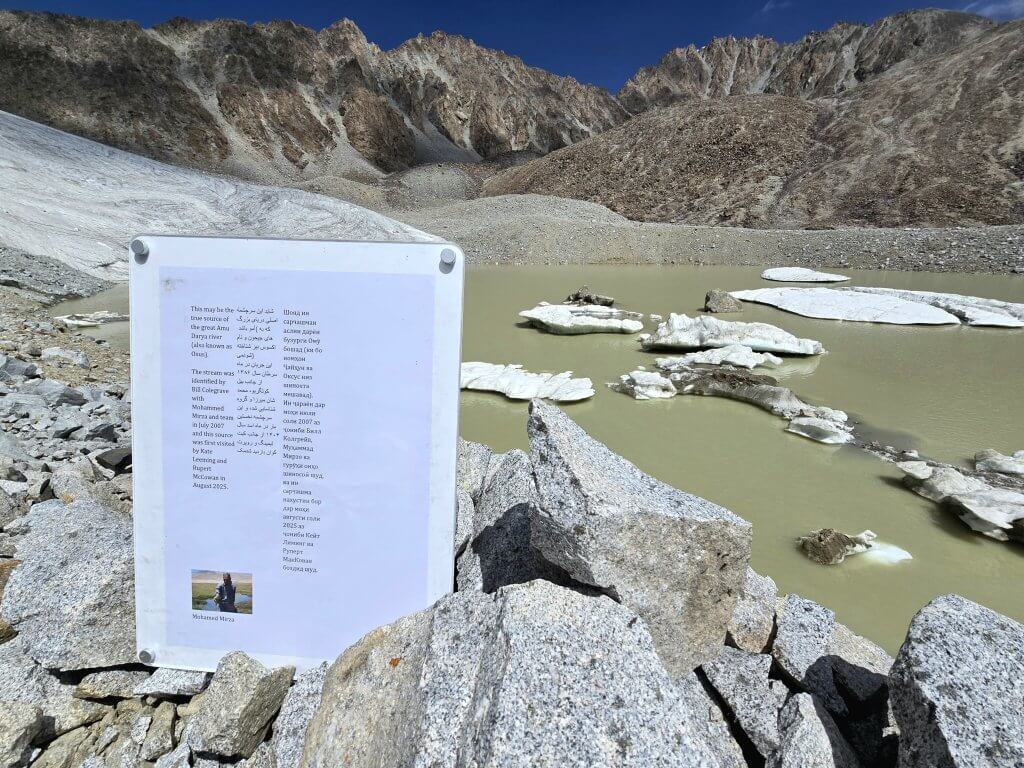

We took time to absorb the moment. The scene – the lake, the glacier and the surrounding wall of mountains – was mesmerising. Our silence was broken by the regular cracking of the nearby glaciers as they melted. In the warmth of the day, water literally poured off the Chelab Glacier into the lake. Small rivulets carved in the ice channelled the flow of water into waterfalls. It felt very appropriate that we made this discovery in the International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation.

My emotions were very mixed. On one hand, I was very proud of my achievement, from taking an idea that I dreamed up to actually bringing a team to the finish line here at the true source of the Oxus. On the other hand I felt overwhelmed. I could feel this was a powerful place but this is also such a fragile, threatened environment. The small icebergs in the middle of the lake floated silently, precariously – their days numbered. Every year now, the glacier recedes a little more.

I felt aware that I was standing in a moment of time within the long history of the search for the source of the Oxus. I imagined, in the time of Marco Polo (13th Cent.) or the Great Game (19th Cent.), glaciers would have dominated the valley and the source would be in a vastly different place, further downstream. I dread to think of the days when there will be no more glacier left to melt. What will that do to the river and the lives of millions of people who rely on its waters? Eighty percent of the water in this river, and the Syr Darya, comes from glaciers.

It is well established that the source of a river must be a permanent geographical feature, not subject to change daily, weekly or even annually. This lake certainly ticks that box. Rupert later explained that the geomorphology of the lake means it is going to remain a lake even after the glacier has gone, he estimates in 20-30 years (depending on ice depth and climate change in the region). Thereafter, following the disappearance of the glacier, the lake will remain as a stream-fed lake for the foreseeable future, although the volume may be somewhat reduced. In the absence of a major earthquake or equivalent, the lake might be expected to stay for 10,000 years or more. Had there been no significant lake here, once the glacier disappeared there would be no true source of the Chelab and Oxus. This lake is one precious jewel!

When cycling around the Aral Sea I saw firsthand what happens to the environment when it is blatantly abused, and learned how the toxic dust doesn’t only affect the health and wellbeing of the local population, it has spread around the world, as far as Antarctica. This has become an issue that affects us all.

The source of the Oxus is a special place. The alarming disappearance of this glacier, as with glaciers around the world, is a result of climate change; caused by human activities around the world, not by local and regional actions as with the Aral Sea. Whether it is local actions causing global problems or global actions causing local issues, we are all in it together. And together we must work to solve and manage these issues.

The historical and religious significance of both the Oxus (Amu Darya) and the Jaxartes (Syr Darya) rivers dates back to the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad who mentioned four rivers that are found in the paradise. These rivers, the four most important in the Arab world, are called Saihan (Syr Darya/Jaxartes), Jaihan (Amu Darya/Oxus), Euphrates and Nile. He mentions that each of these rivers have water that is pure and sweet to drink from. It is believed that these rivers will never run dry and will always be full of life-giving water for the people who inhabit paradise. This hadith (words from Muhammad) teaches people to strive for a place in paradise by doing good deeds throughout our lives so we can enjoy its blessings forever.

We did drink from the glacial streams of the Oxus/Jaihan/Amu Darya and the Jaxartes/Saihan/Syr Darya but nowhere else along these rivers is there water I would drink. There is the very real threat that these two rivers, with the accelerated melting of the glaciers (due to climate change) in the Tien Shan, Pamirs and Hindu Kush, with the mismanagement of the water resources, and with the compounding need for water by the growing populations, could run dry, or virtually dry. Doing good deeds to strive for a place in paradise has a very literal meaning in the case of the Aral Sea Basin.

We were aware that the 28 streams we needed to cross on the return trek were rising by the hour as the ice melted in the warm afternoon sun and hurried back to camp before it became too difficult, and then back to Aqtashtoq. It took over four hours to drive the 80km back to Sarhad and nine hours to drive the 192km from there to Ishkashim the following day, such is the state of the tracks and roads that I had endured on a bicycle.

Back in Kunduz we briefly crossed paths with Sophie Ibbotson and her colleague Kamila Erkaboyeva who, by total coincidence, were heading out to explore the Chelab Stream in search of the true source of the Oxus! After Rupert and I shared the details of our exciting discovery of the source of the West stream of the Chelab (the true source of the Oxus), they went on, armed with our information and that of Bill Colegrave’s 2007 findings, to explore the East branch. We hope to collaborate to bring greater knowledge and understanding about this very special and remote region at the roof of the world.

PLEASE TAKE ACTION

THIS IS THE LAST MONTH OF MY CAMPAIGN FOR WATER.ORG. WE HOPE MORE PEOPLE WILL CONTRIBUTE AND GIVE WATER.ORG A BIG BOOST!

Support my Water.org fundraiser to help bring safe drinking water and sanitation to the world: Just $5 (USD) provides someone with safe drinking water or access to sanitation, and every $5 donated to my fundraiser will enter the donor into the Breaking the Cycle Prize Draw.

Thanks to ZeroeSixZero, you can open this link on your phone and select “add to home screen” and the map will become and app. You can then keep updated in real time.

Support my Water.org fundraiser to help bring safe drinking water and sanitation to the world: Just $5 (USD) provides someone with safe drinking water or access to sanitation, and every $5 donated to my fundraiser will enter the donor into the Breaking the Cycle Prize Draw.

An education programme in partnership with Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants, with contributions from The Royal Geographical Society and The Duke of Edinburgh’s International Award Australia. We have created a Story Map resource to anchor the programme where presentations and updates will be added as we go.