Newsletter Subscribe

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

6th – 9th July | Murghab to Langar | Distance: 318km | Total Distance: 6859km

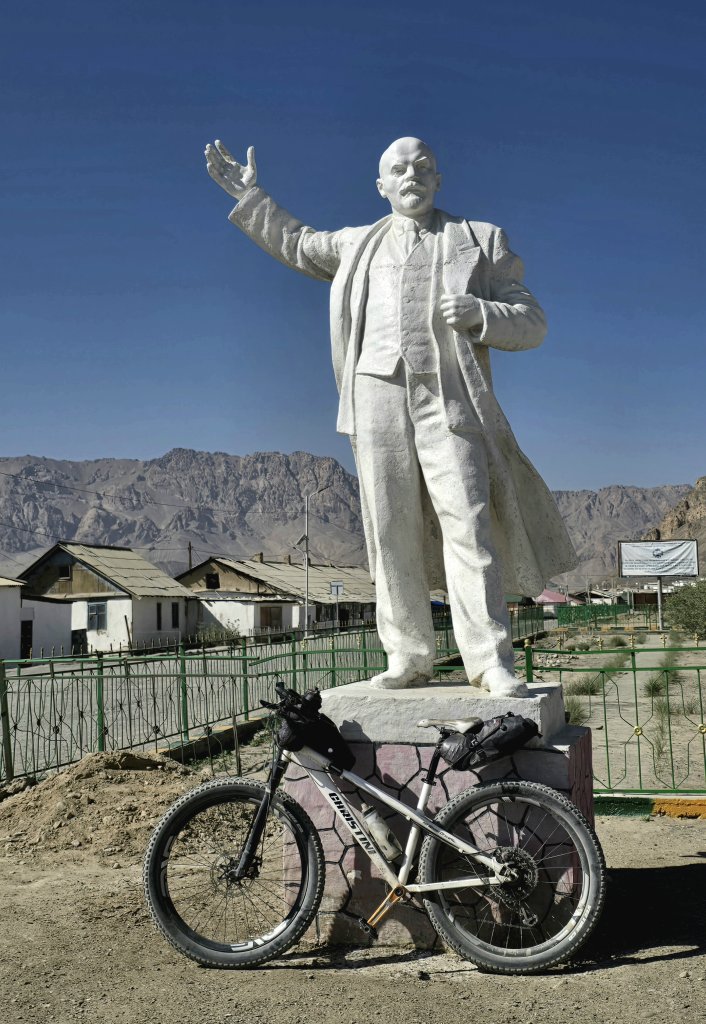

Murghab town, the main centre in the eastern Pamir (population 6000), on first appearances is a desolate place where temperatures can drop to -50C in winter and reach 30C+ in summer. At 3650m, it is considered a high altitude desert regularly receiving strong winds. At the end of the 19th Century, the Pamir region was a confrontation zone between the world powers – Russia, British Chinese empires. Imperial Russia founded Murghab in 1892 because of its strategic location strengthening its military presence against China and the British Empire claims (Pakistan, Afghanistan). The Soviets wanted to strengthen their claim by closing the borders and building the Pamir Highway as a military supply link for the region. The Soviets also ensured the people of Murghab were well taken care of, making the town a “choice” destination, despite the harsh conditions.

Murghab was a much needed physical rest day and a pit stop – blog writing, shopping, planning the next phase, and washing, etc. Karim organised our permits for Lake Zorkul National Park and helped me change money. Murghab will also be remembered for the vicious mosquitoes that mauled any exposed skin from the mid-afternoon until after dark.

The plan was to continue following the Murghab River upstream, through the mountains to Tokhtamish where it changes to become the Aksu River that flows out of Lake Chaqmaqtin in the Little Pamir – the eastern part of Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor. The aim was to follow the rivers as far as possible and then cut through remote tracks towards Lake Zorkul thus following the longest tributary of the Amu Darya as far as possible and then connect with another of the main sources of the great river. The border areas with Afghanistan and China are militarily sensitive regions.

We had no choice but to return to Murghab and take an alternative route that keeps the line of my journey connected.

Karim and I came up with an alternative plan that was just as good. From Murghab we returned to the turn-off to where we previously visited the Shakhti Cave Drawings. I cycled from the highway, connecting the line of my journey. Sometimes curveballs happen for a reason – this alternative route was one of the highlights of my journey so far, even though it was perhaps the toughest physically.

At this point, Karim said I had to make a choice – aim for a settlement with a natural spring called Jorty Gumbaz (13km away), or head for where we originally wanted to get to on the edge of the Lake Zorkul National Park, a further 18km away (31km in total). I was feeling very tired, my legs full of painful lactic acid (the lack of oxygen at this altitude limits recovery). We had enough time and I decided to do the 31km to keep on schedule, knowing there were some more serious challenges over the next couple of days. I wanted to give myself the best chance to keep on track.

After the settlement, I was not only facing another mountain pass of over 4400m, I was confronted by a powerful head wind. The gusts just about blew me off the track many times. The climb wasn’t as steep as the first of the day, but I was struggling. I broke the climb into sections, baby steps actually, but the little used track was a mess of stones, muddy sections, meadow grass and stream crossings. I was barely managing to stay on the bike…but I kept going.

I passed the snow line. Just small chunks of snow were left melting into the diminishing stream. The team was very supportive – the cold wind, the rough track and the altitude made this an extreme personal battle for me.

The two yurts at Karajulga belonged to a Kyrgyz family who live there during the summer and as the season turns, they pack their yurts and drive their 20 yaks and 100 goats to Murghab for the winter. Omar, was the head of the family and welcomed us in to his home.

I was really looking forward to reaching Lake Zorkul, one of the sources of the Amu Darya. However, It didn’t get easier! The high plain was not flat, the track was as rough and wet as it gets and I had a powerful headwind again, all day.

Right through the day, there were many water crossings to make. Some were easy while others required me to cycle through the water, or walk upstream to find a narrower crossing place. I had two major crashes. The first one, after about 15km, was the worst. I hit a large round stone in the deeper part of a stream crossing, tried to fall to the side rather than the middle of the stream, and the boney crest of my right hip landed squarely on the point of a large granite rock. It really took my breath away. I crossed the stream (with wet feet) and assessed the damage. Standing straight and walking really hurt, but when flexed in the cycling position I was still able to ride, though not without pain. The second big crash, this time in front of my team, was also when trying to cross a stream. I started too close to the water’s edge and didn’t have enough momentum, hit a large, round stone and duly landed hard on a bed of rocks. I jarred my bad knee and lost some skin, but this wasn’t so serious. My hip is still sore – I think I have bruised the bone.

I was excited to finally see Lake Zorkul, one of the key sources of the Amu Darya. The lake and region has some important history. There is an assumption that Marco Polo passed through the valley on the way to China. He gave the first account of the very large sheep in the region that now bear his name.

The true source of the Amu Darya (known as the Oxus River in antiquity) has been a matter of conjecture for at least 200 years; since the Great Game. Lt Wood of the Indian navy first asserted that it was Lake Zorkul (which, of course, he named Lake Victoria) in 1858. The region became famous for its part in the Great Game between the British and Russian empires. In 1895, the Pamir Boundary Commission established its first pillar at the eastern end of Lake Zorkul to define the border between Afghanistan (British protectorate) and the Russian Empire.

The track remained much higher than the level of Zorkul Lake (4126m above sea level)) and kept about three kilometres from the water’s edge. I assumed this is because the landscape becomes too boggy, especially as the snow melts in spring. The boundary pillars and the border are both still there, although, with my path being so far from the lake’s edge, I wasn’t able to see the pillars.

I wanted to get to the shoreline and the shepherd was able to direct us down the only route, he said, where it was possible to cycle/drive to the lake. It was a cross-country ride with only the occasional faint wheel track to spot. It was worth the effort, but as soon as we started to move through the grasses and low bushes beside the lake, the mosquitoes were out in force, spoiling the occasion. As I finished a piece to camera, a huge swarm of marauding mozzies descended like a noisy plague in a horror movie. In fast motion we we packed up and were on our way back to the shepherd’s property. Maybe that’s why few venture to the shoreline of the lake.

The wind died down overnight but soon sprung up again in the morning.

The Zorkul Lake track ended with 4km flanked by razor wire and a GBAO checkpoint (checking our permits were in order) at Khargush. From there I turned back onto a more major road, however the surface was disappointing. It was terrible and, even though I was mostly heading downhill, I struggled to do more than 13km an hour into the horrific headwind that whistled up the valley.

About 15km from Langar, our destination, was a wild river tributary. It is preferable to cross the stream in the morning before the sun melts more of the glaciers away. But we arrived at 6pm and the river was raging.

Karim knew of the dangers and was appropriately worried. However he had a glint of steely determination in his eye. He’d worked out what he needed to do but it was going to be tight. There were no houses or places to camp for the 70km before the river and we had no proper food left. Georgia and I were asked to ford the river because the extra weight would jeopardise the success of Karim getting the vehicle through. He first crossed half of the stream and stopped in a spot where the vehicle formed a bridge for Georgia and I to hang on to over a particularly difficult bit. Then we had to get across the next part, over a large pipe and rocks that were difficult to see in the opaque, silty water. We made it! Now it was Karim’s turn. The first attempt failed as the rear wheels were left spinning with nothing to grip. He reversed a little and then gave it full revs, just making it across. It was quite an emotional reunion, but we made it across.

It was a race against the light to cover the final 15km, mostly downhill, with the roughest track imaginable on what is meant to be a major road. I had to concentrate hard to keep the bike under control and try to avoid as many of the obstacles as possible, including being chased by aggressive dogs at one point. I was rattled to pieces and so was the bike.

We made it to Langar, where the Pamir River and the Wakhan River (that flows from the Wakhan Corridor in Afghanistan) meet to become the Panj River. It was the first village we’d seen since Murghab and the site of our guesthouse with a warm shower and good food was most welcome.

Thanks to ZeroeSixZero, you can open this link on your phone and select “add to home screen” and the map will become and app. You can then keep updated in real time.

Support my Water.org fundraiser to help bring safe drinking water and sanitation to the world: Just $5 (USD) provides someone with safe drinking water or access to sanitation, and every $5 donated to my fundraiser will enter the donor into the Breaking the Cycle Prize Draw.

An education programme in partnership with Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants, with contributions from The Royal Geographical Society and The Duke of Edinburgh’s International Award Australia. We have created a Story Map resource to anchor the programme where presentations and updates will be added as we go.