Newsletter Subscribe

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

Days: 94-101

Dates: 12th – 19th September

Distance: 732 km

Total Distance 2023: 7089 km

Total Distance (2021 + 2023): 8617 km

Tracking map by ZeroSixZero: https://z6z.co/breaking-the-cycle-australia/

My apologies for taking so long to publish the final blog – here it is:

Having just completed an intense week of cycling to cover the 731km from Newman to Mount Augustus through the East Pilbara and Ashburton regions, and with the prospect of a similar challenge to reach the finish at Steep Point, the temptation was to have a complete rest day camping beside Mount Augustus. However, I had planned to climb Burringurrah, as it is known by the local Wajarri people, and would have regretted missing the opportunity. The enormous inselberg (lone mountain) rises 717m above the eroding plains, 1105m above sea level.

To beat the heat, Mark, Russell and I made an early start, setting off from the head of the hiking trail at 5.30am, guided by the light of our head torches. The first 1.2km were of moderate difficulty, and as the early morning light diffused the darkness, I could gradually make out the rocky trail.

The next 2.8km involved a real scramble as we ascended a further 400m up a steep, rocky path. Every so often we stopped for a drinks break, to film or simply to take in the beautiful surroundings. As I climbed higher and the sun appeared through the morning clouds, the warm, orange colours of the mighty sandstone rock became more intense and fiery.

I had been struggling with a painful lower back when walking (from cycling 7-8 hours a day without enough rest or stretching), and I had been worrying about how I would manage on the climb carrying a small backpack up the mountain. To my relief, it was manageable, so I pressed on, trying to adapt to this different form of activity.

After about 3km, the gradient rounded off and the second half of the 6.25km climb became much easier, until the final scramble to reach the summit. It was a wonderful feeling to be atop the world’s largest rock (monocline), 1107m above the plains. In the distance were much lower hills, gradually succumbing to the same forces of erosion that had also shaped Mt Augustus. We celebrated our climb and spent about 45 minutes relaxing and taking in the views. The vastness and subtle colours of the landscape were difficult to capture from behind the lens, but we gave it our best shot.

The return journey was the part I was dreading because of my damaged knee. I had brought my special knee brace to try to offload some of the stresses on my knee during the descent. While it offered some protection, I really struggled over the steep section and had to work my way back to base patiently and painfully.

Burringurrah was an incredibly important place for the Wajarri people, particularly in times of drought. Water flowing off the 10km-long rock has formed permanent springs around its base, supporting the area’s biodiversity. This more abundant environment has provided the Wajarri with food and water for thousands of years, and the many caves made natural shelters.

There was no time to rest, as I had to keep moving and average 115km a day for the next four days to make reaching the finish more achievable. On the evening after the Mt Augustus climb, a violent gust of wind actually broke my tent, causing it to collapsed on top of me. I had to sleep on the back seat of Neil’s vehicle.

That event was a bit of an omen for the day ahead, Day 95. When I set off, there was a moderate headwind, but I could still progress at a reasonable speed. After the first 30km, the wind steadily increased, until I was down to 12km/hr in the powerful gusts. Just before my first break, Martin’s drone was caught in a strong gust of wind; like an aeroplane on a doomed flight path, I watched it crash out of control into a tree. Fortunately, it survived with only a few superficial chips to the propellers.

About 50km west of Mt Augustus, we reached the Old Bangemall Inn, established in 1896 to serve gold prospectors. There, we joined a section of the Charles Kingsford Smith Mail Run. Over the next two days, we followed it for 240km as far as Gascoyne Junction. In 1924, fresh from a stint as a pilot for Australia’s first commercial airline, Charles Kingsford Smith and Keith Anderson bought a truck and set up business as the Gascoyne Transport Company. Kingsford Smith figured that, with his mechanical knowledge and the new-fangled technology of motorised transport, he could out-do the camel trains and horse wagons on many inland delivery routes. He also thought that, if he was right, the money he would make would finance his dream – of being the first to fly across the Pacific.

By the second stint of the day, I was totally struggling with the wind, the heat (35°C), and being sore from using different muscles during the hike. It was a case of just hanging in there and making the most of any shelter I could find from the wind. To make it easier mentally, I broke the afternoon into smaller 15km sessions to make it easier mentally.

Right when the team thought we should stop, I had to insist to put in another 8km and at least cover 110km for that day. I was mindful that the wind could play a big role in these final days, so I wanted to get as many kilometres on the board as I possibly could.

I woke up feeling pretty sore all over, particularly in my back and hips. This had been the case for about a week. My knee was still swollen from the descent of Mt Augustus. I am used to managing the knee problem and carrying on regardless. However, the back/hip issue is something that will require rest (after the expedition) and some physio attention. The good news was that the weather was kinder, with only a gentle breeze and cooler temperatures (29°C).

The gravel Cobra-Dairy Creek Road was pretty good quality, and after only a few kilometres, I reached the Yinnetharra Station homestead and the mighty Gascoyne River. Although I was still hundreds of kilometres from the mouth of the Gascoyne, the ephemeral river was already impressive. From there, all the way to Gascoyne Junction, 180km away, I crossed many large creeks lined with majestic river gums that were tributaries of the Gascoyne River. The volume of water flowing through these creeks and down the Gascoyne almost defies my imagination.

After passing the Dairy Creek Station homestead, I turned west onto the Carnarvon-Mullewa Road towards Gascoyne Junction. This route is a part of the Wool Wagon Pathway, a stock route for graziers to drove their sheep and transport wool to the port to sell.

To my surprise, sections of the Carnarvon-Mullewa Road had been sealed, and with a favourable tailwind, I reached Gascoyne Junction in quick time. Gascoyne Junction is located where the Gascoyne and Lyons rivers join. The biggest town we have seen since Paraburdoo, the community has a population of 149 people! We made it a lunch stop before heading south on the Pimbee Road.

For the second half of Day 97 and all of Day 98, I wound my way through station country in the heat (36°C), first along the Pimbee Road. We camped in a gravel pit near the abandoned Towrana Station, before turning off onto the Meedo Road the next day.

The Meedo Road was smaller, a little sandier, and more challenging between the Pimbee Road and Meedo Station, but also more interesting. To the east of the homestead, I passed through a landscape dotted with salt pans and low sand dunes. The Wooramel River, another impressive ephemeral river, was a highlight just east of the homestead.

Between the homestead and the Northwest Coastal Highway, the quality of the road really improved, but the southwesterly wind strengthened in the afternoon, making it very challenging to reach my goal of Wooramel Roadhouse. I was getting pretty tired and just tried to keep the pedals turning.

With only three days to go, I was getting quite excited. However, the forecast of the notorious southwesterly trade winds had me worried. Leaving the Wooramel Roadhouse on the highway I had to push into it head on for 75km before turning west to enter the Shark Bay World Heritage Area. Turning the corner, the southwesterly wasn’t such an issue, as the scrubland provided some shelter from what was then a crosswind.

Upon reaching Hamelin Pool, it was a relief to see the ocean again—for the first time since Cape Byron at the start of this expedition. Hamelin Pool supports a unique ecology because of its hyper-saline waters. The microbial mats and stromatolites located on its southern beaches are among the features that earned the region its World Heritage listing.

Microbial mats and stromatolites are diverse and complex ecosystems where different species of bacteria and other microbes work together in symbiotic communities. Under certain conditions, these communities can trap particles and create stone. When this happens, microbial mats become microbialites. Sometimes microbialites form taller, layered structures called stromatolites. The stromatolites and microbial mats in the shallows of Hamelin Pool are among the most diverse in the world, offering a glimpse into what marine ecosystems looked like three billion years ago. Therefore, microbial mats have been around for over 75% of the Earth’s history! Over the last two billion years, cyanobacteria in microbial mats influenced evolution by breathing oxygen into the atmosphere. Without these primitive life forms, we would not have evolved.

I had stopped off at Hamelin Pool and visited the stromatolites during my Great Australian Cycle Expedition in 2004, before the viewing boardwalks were destroyed in a cyclone. This time I had to be content watching the sunset over Hamelin Pool and the stromatolites, whose habitat is the shallow waters, just off the beach.

From Hamelin Pool, I continued along the Denham Road for about 12km until I reached the turning towards Useless Loop (salt mines) and Steep Point – 148km to go.

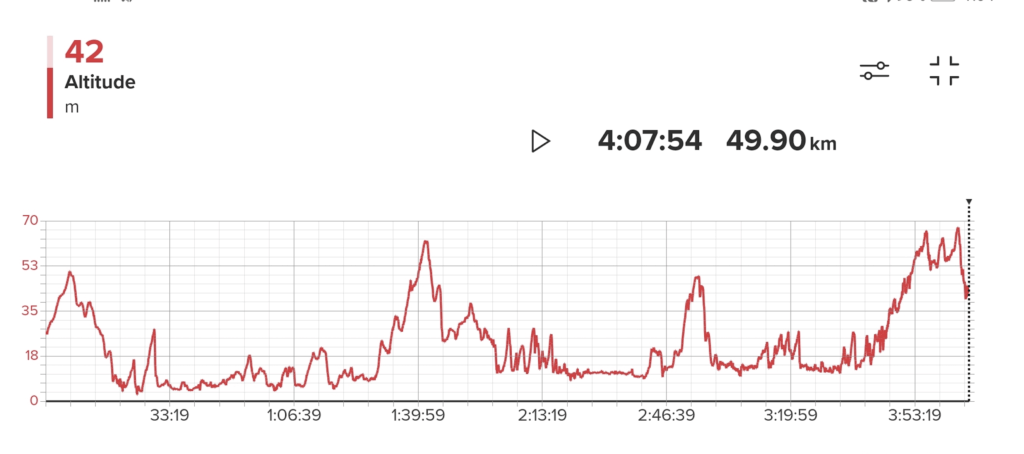

I was pleasantly surprised to discover that the first 22km of the sandy gravel road had been sealed. The route was like a rollercoaster, as the road bisected the direction of the sand ridges. As I pedalled west, the surrounding bush gradually disappeared, leaving there me exposed to powerful gusts of wind, especially when I crossed the salt pans and later reached the coastal heathland.

The whole of the penultimate day was a battle: against the wind, the corrugated, hilly road, and my extremely tired legs. I had to get to Steep Point the following day, so there was no choice except to push on so I was within “striking distance”. We had been aiming for a tiny camp spot we’d heard about, but there was no shelter anywhere – it was all coastal heathland, the scrub no more than a metre high. It was so windy, we didn’t even try to pitch my tent. Mark’s tent was pegged to the ground with every peg we had and tied to the vehicles. The vehicles gave enough protection for us to cook – just – and I spent my last night sleeping in the back of Neil’s vehicle. It wasn’t how I’d imagined the last night of the expedition to be.

I had been warned that the ride through Edel Land to Steep Point was going to be a big challenge. I was prepared mentally for the fight, even if my body was exhausted. After a few kilometres, I passed the end of the well-maintained Useless Loop Road – at the Useless Loop (salt mine) turn-off – and immediately the road turned into horrific corrugations and mostly sandy conditions (except for the salt pans).

In the first sections, there was just nowhere for me to cycle as the whole road was a mess. I continually tried to find the smoother sections on the very edge, but often I would be swiping against the scrub that encroached onto the track. Mostly, I just had to absorb the bumps. After 18km, we reached the big sand dunes, and I dropped my tyre pressure right down to about 5psi. At this pressure, the fatbike tyres really grip the sand. The all-wheel drive system remained switched on and gave a little more traction when the back wheel slipped.

I had not had to walk my bike over any sand dunes on this journey so far, and I was determined to keep it that way, even though these dunes were totally chopped up by vehicles. There were approximately 7km of giant, soft sand dunes with steep ascents and descents, but I managed to pedal the whole route. From there, the track took an undulating, bumpy course towards the beach. We had one final tea break to take it all in before tackling the last 16km – along the beach, then back onto the track. We checked in at the ranger’s house and then turned towards the country’s most westerly tip. At times, it felt as if the rollercoaster would never end. These sharp climbs served to drain every last drop of energy from my body.

Steep Point is an incredibly beautiful yet wild place, completely exposed to the elements, the cliffs drop sheer into the Indian Ocean. Large waves continually crashed into the rocks, and the wind created white caps on the ocean for as far as I could see. It was a challenge just to stay on the bike.

I reached the sign at Steep Point at around 1pm, and we spent some time celebrating and filming the moment. I felt a strong symmetry in finishing my Breaking the Cycle in Africa expedition at Cape Hafun, Somalia, (Africa’s most easterly point) and the end of this continental crossing at Steep Point (Australia’s most westerly point). The two landmarks are connected by the Indian Ocean, and both of my journeys ended in similarly windy conditions with a sheer drop to the ocean. As with the end of the African expedition, I struggled to lift and balance my bike in the gusts of wind.

All expeditions have their challenges, but never have any of my journeys presented as many curveballs as this one – my broken collarbone and then interstate COVID-19 restrictions in 2021, a month’s delay before we could start this one due to a health issue with a support team member, late rains blocking the roads and further delaying the 2023 start, the unseasonal flooding of Eyre Creek preventing me cycling across the Simpson Desert and along the Finke River, the heavy rains that blocked the Oodnadatta Track and forced me to take the only sealed route all the way south to Port Augusta, a three-week delay due to a major vehicle breakdown near Coober Pedy, and several other problems that required me to adapt my schedule/route. Somehow, through all of these issues, the we found a way through to finish only four days later than my original plan. I’d had to adapt the route and cycle more intensively than I had planned, but the adventure found its own path, and the key purposes of the expedition have been achieved. That makes me very proud of this one.

We drove to Denham to film an amazing initiative by the Malgana people of Shark Bay – that will be covered separately.